Until recently, subsection 52 (5) of the Condominium Act, 1998 (the “Act“) stated:

(5) An instrument appointing a proxy for the election or removal of a director at a meeting of owners shall state the name of the directors for and against whom the proxy is to vote.

This provision was widely understood to mean that the right to vote in an election of directors could not be exercised by the proxy, but was exclusive to the owner or mortgagee who appointed the proxy.

In November 2017, the provincial legislature repealed this provision,[1] otherwise amended the section of the Act that governs methods of voting (section 52) and introduced a new, mandatory form of instrument appointing a proxy (a “proxy form“), the quality of which may be inferred from the fact that the word “mortgagee” is misspelled in a particular instance on the first page.

These changes have raised the following questions, among others:

- In cases where the person who completed the proxy form (referred to below as an “owner”) has not provided instructions in the proxy form with respect to the election or removal of a director, does the proxy have the authority to vote in that respect? Should the proxy be given a ballot in those cases?

- If the proxy does have the authority to vote in those cases, what instructions can the owner provide in the proxy form to override the proxy’s authority?

By reference to the relevant provisions of the Act, the language of the proxy form and a series of examples, this article will serve to provide our best answer to these questions and comment on the implications, and to provide an additional comment on the appointment of proxies under the proxy form.

- Does the proxy have the authority to vote in an election?

In our view, unless the proxy form contains an intelligible instruction from the owner with respect to an election, the proxy must be given a ballot to vote in the election.[2]

Our view in this respect flows from the recent amendments to the Act. The legislature repealed the former subsection 52 (5), as mentioned above, and did not replace it with a corresponding requirement in the regulations, or for that matter, in the mandatory proxy form. There would have been little reason for these changes if the legislature did not mean to give owners the option of authorizing their proxies to vote in an election.

In addition, the former subsection 52 (1) stated only that “(on) a show of hands or on a recorded vote, votes may be cast either personally or by proxy”, but subsection 52 (1) now states:

52 (1) Votes may be cast by,

- a show of hands, personally or by proxy; or

- a recorded vote that is,

- (i) marked on a ballot cast personally or by a proxy,

- (ii) marked on an instrument appointing a proxy, or

- (iii) indicated by telephonic or electronic means, if the by-laws so permit. (emphasis added)

Our conclusion is reinforced by the language used in the section of the prescribed proxy form that defines the scope of the proxy’s authority. It provides the owner with two options for how much authority to give the proxy, the first of which is presented as follows:

Ostensibly, an owner may select this first box, or sign or initial next to this option, or both,[3] if the owner intends the proxy to be counted for “quorum only” and to only vote on procedural issues (e.g., a motion to close nominations).[4] If the owner selects the second option, however, the owner authorizes the proxy to vote “with respect to all matters that come before the meeting,” subject to the instructions set forward in the rest of the proxy form:

Here, the “Instruction for person filling out this form” (referred to below as an “Instruction for Owner“) expressly tells the owner that by selecting this option, the owner will authorize the proxy to engage in voting for candidates, subject to whatever instructions the owner provides below it.

Along with the changes to the Act itself, this reference to “voting for candidates” makes it clear that if the owner selects the second option and does not provide voting instructions in the proxy form, the proxy must be allowed to cast a ballot in any election held at the meeting.

Clear as that may seem, some uncertainty is introduced by the Instruction for Owner that follows every section of the proxy form which relates to an election:

At least one other firm has expressed the view that by providing this Instruction for Owner in the sections that relate to electing a director, and not providing a similar Instruction for Owner in the section that relates to removing a director, or the section that relates to other, specific matters, the legislature must have intended to preclude proxies from voting in an election, even in the absence of voting instructions from the owners.

That aspect of the proxy form is insufficient, in our view, to overcome the effect of the changes described above. Subsection 52 (5) already precluded proxies from voting in elections, but the legislature repealed it. Subsection 52 (1) now expressly permits ballots to be cast by proxies and imposes no restriction on the subject-matter of those ballots. The proxy form cites “voting for candidates” to provide an example of a matter in respect of which owners may authorize their proxies to vote.

Moreover, we find it hard to imagine the purpose that would be served by permitting proxies to vote in respect of the removal of directors, but not in the election of replacements, or in an election otherwise.[5]

- What instructions can the owner provide in the proxy form to override the proxy’s authority to vote?

We address this question by reference to a series of hypothetical examples below, each of which is subject to assumptions that (a) the owner has, by selecting the “second option” mentioned above, authorized the proxy to vote, subject to the owner’s instructions, in respect of all matters that come up at the meeting; and (b) the only matter on the agenda for the meeting is an election of a director to a single vacancy on the board.

Complete Instructions

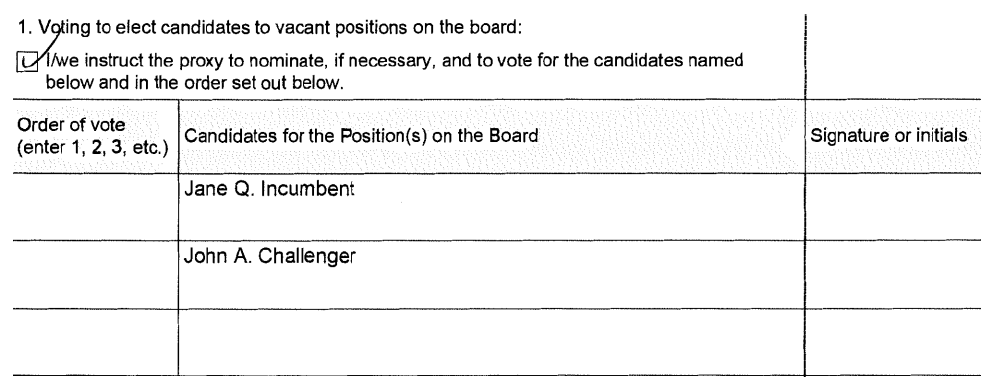

In some cases, the owner has clearly voted by way of the proxy form itself:

This example, in which the stars are perfectly aligned, includes several, clear expressions of the owner’s intention. The owner has marked the box to indicate that the owner instructs “the proxy to nominate, if necessary, and to vote for the candidates named below and in the order set out below.” (We refer to every box of this nature below as an “operative box” because, if marked, it purports to trigger the operation of the rest of the section.) The owner has also printed the names of the candidates, initialed next to those names and marked the numbers “1” and “2” to indicate order of preference.

Incomplete Instructions

The paramount question to be considered in reviewing a proxy form is whether the owner’s intention can be discerned from it.

Accordingly, in our view, as long as the owner has included some sort of discernible instruction in the relevant section, the vote of the owner is recorded in the proxy form itself and the proxy should not be given a ballot.

That will be so even if the owner only marks the operative box in a proxy form pre-populated with the names of declared candidates and circulated with the notice of meeting by the corporation:

The important take-away from this example is that the owner has expressly instructed the proxy to vote for the candidates named below and in the order set out below. The proxy form itself serves as the ballot, according to which the owner voted for Jane Q. Incumbent or failing Jane Q. Incumbent, John A. Challenger, and the proxy is deprived of any discretion.

The same analysis will apply if the form has not been pre-populated and the owner does not mark the operative box, sign or initial in the spaces provided or mark numbers in the “Order of vote” column, but otherwise prints the names of candidates in the spaces provided:

In the preceding example, the handwritten names disclose the owner’s intention to vote for those candidates. Nothing in the proxy form would have suggested to the owner that a failure to check the operative box, or the lack of a signature or initials, would invalidate the instruction embodied in the handwritten names, and common sense would suggest that the names appear in order of preference, such that the lack of numbers has no effect: the proxy form itself serves as the ballot.

No Instructions

As mentioned above, if the owner selects the second option and does not provide an intelligible instruction in the proxy form, the proxy must now be given a ballot to vote in the election. Insofar as this change creates fresh opportunities for abuse by less scrupulous members of the community, the legislature appears to have determined that the cost of those abuses is outweighed by the benefit of allowing owners to reserve their electoral votes until the time of the meeting.[6]

The proxy’s authority to vote in an election, together with the language contained in the corresponding Instruction for Owner, may also create a problem for corporations that engage in the common practice of pre-populating a blank or “executable” version of the proxy form with the names of candidates.

This problem will not occur where the corporation creates a sufficient number of spaces for the owner to print the names of candidates, but does not pre-populate those spaces with names, and the owner does not provide voting instructions in the proxy form: in those cases, assuming again that the owner has authorized the proxy to engage in “voting for candidates and other substantive matters”, the proxy must receive a ballot.

If the spaces are pre-populated with names and the owner does not provide instructions, however, the Instruction for Owner tends to muddy the waters:

In this example, the proxy must be given a ballot to vote in the election because the owner has not provided any voting instruction at all, but the Instruction for Owner has explicitly told the owner that the proxy “may only vote for individuals whose names are set out above … your proxy will vote in the order set out above up to the number of positions that are available.”

Reading that Instruction for Owner may have created a reasonable expectation in the mind of the owner that their vote would be cast, first, for Jane Q. Incumbent, or alternatively for John A. Challenger. The owner could then be unpleasantly surprised to learn, after the meeting, that the corporation gave a ballot to the proxy, as required in the absence of any instruction, and the proxy voted to elect, for example, a random tenant who nominated themselves at the meeting.

The courts have held that under section 135 of the Act, an applicant for relief from oppression must demonstrate, among other things, that a reasonable expectation of the applicant was infringed.[7]

Accordingly, for the purpose of preparing an executable version of the proxy form to be distributed to owners with the notice of meeting, the corporation should consider including a sufficient number of spaces for the owner to print the names of candidates, but not pre-populating those spaces with names. The corporation is already required to state, in the mandatory form of notice of meeting, the names of all individuals who declared their candidacies within the required time. Unnecessarily adding those names to an executable version of the proxy form might only serve to compound the confusion that the proxy form is causing and create a reasonable expectation of the sort mentioned above.

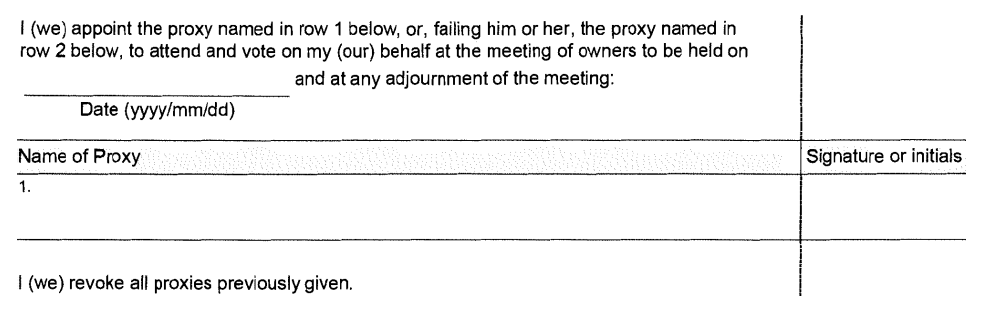

- Appointment of a Proxy Under the Proxy Form

The second page of the proxy form contains a space for the owner to appoint the proxy for the relevant meeting:

An owner may forget to print the name of the proxy in this space, in which case the proxy form is invalid and cannot be counted for quorum or any other purpose.

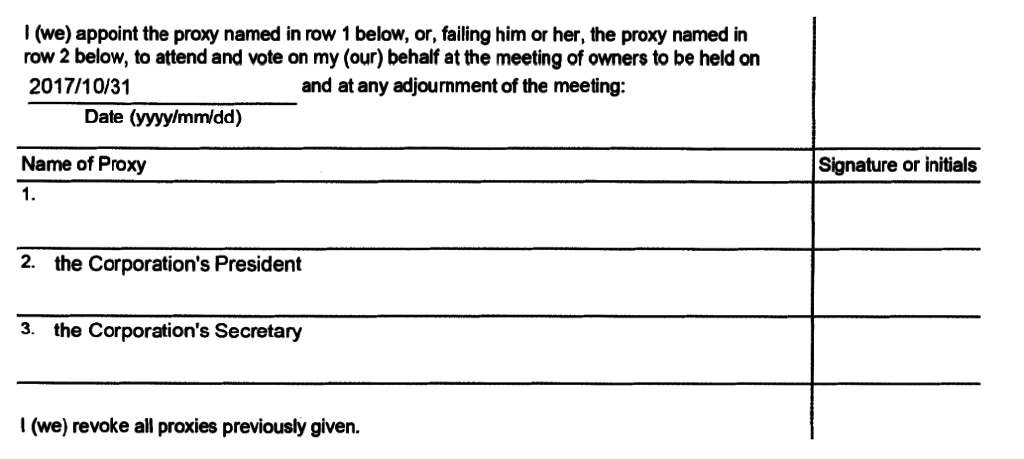

Accordingly, for the purpose of preparing an executable version of the proxy form to be distributed to owners with the notice of meeting, the corporation should consider adding at least one extra space, and pre-populating that space with at least one alternative or “back-up” proxy:

In this example, even if the owner forgets to name a proxy in the first space, as long as the corporation’s president or secretary attends the meeting, the proxy form cannot be invalidated for the lack of a proxy; in this section of the proxy form, adding extra spaces and pre-populating them with “default proxies” can only help to ensure that the meeting will achieve quorum and not need to be adjourned.

Prepared by Michael Campbell

© Deacon, Spears, Fedson + Montizambert, 2018. All rights reserved.

[1] That the legislature did so pursuant to the Protecting Condominium Owners Act, 2015 was surely not intended to be ironic.

[2] The balance of this article deals only with elections, but our comments in that respect may be understood to apply equally to the removal of a director.

[3] If the first box is checked, it does not matter whether the owner signs or initials in the space provided next to that option because the proxy form contains nothing to alert the owner to the potential consequences of not signing or initialling in that space, and the same can really be said for every other “Signature or initials” space in the proxy form.

[4] If the owner selects this first option and proceeds to include specific voting instructions elsewhere in the proxy form, since the owner may have understood the phrase “routine procedure” to include such matters as an election of directors, it raises the question of whether the instructions are valid and the owner’s vote should be counted. In that case, the obscurely-positioned warning that “(if) this box is checked, the rest of this form should not be filled out” would likely be an insufficient basis on which to discount the owner’s vote.

[5] It seems more likely that the Instruction for Owner provided in the section which relates to replacing a removed director was intended to “cover” both removal and replacement.

[6] One might question the value of that benefit in light of the fact that the corporation is now required to give a preliminary notice calling for candidacies to be declared.

[7] See, for example, Metropolitan Toronto Condominium Corporation No. 1272 v. Beach Development (Phase II) Corporation, 2011 ONCA 667 (CanLII), at para. 6, citing BCE Inc. v. 1976 Debentureholders 2008 SCC 69 (CanLII), SCC 69, [2008] 3 S.C.R. 560 with approval.