In November 2017, the Government of Ontario (the “Province”) repealed the former subsection 52 (5) of the Condominium Act, 1998 (the “Act“) and introduced a new, mandatory form of instrument appointing a proxy (a “proxy form”), the fixed language of which produced a serious question, among others, as to whether a proxy so appointed would be entitled to vote in an election if the appropriate box was checked and the executed proxy form did not contain voting instructions.

On April 6, 2018, we published an article that provided our best answer: yes, in those circumstances, despite the unqualified instruction contained in the fixed language, to the effect that the proxy could only vote for candidates named “above” in the executed form, the proxy would be entitled to vote by ballot.

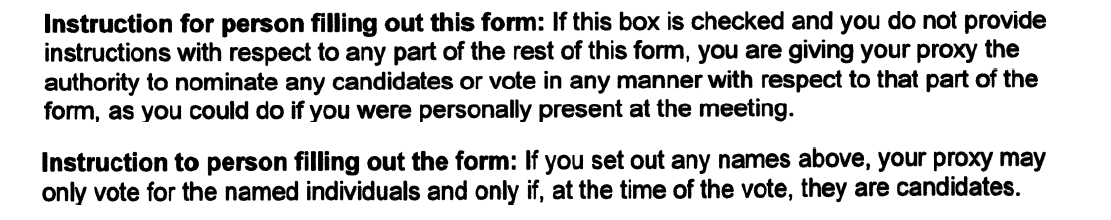

On or around May 8, 2018,[i] the Province introduced a revised proxy form in which the previously-unqualified instruction (and source of confusion) had been qualified, and the fixed language had otherwise been changed to reinforce that conclusion:

It has become apparent that the proxy form continues to have a significant flaw, however, notwithstanding these notable improvements.

Specifically, in the electronic version, there appears a shiny, attractive button, at the top of the first page, the clicking of which leads to the clearance of any data previously entered and allows the entire proxy form to be expanded and printed without a selection having been made as to the business of the meeting, as if all business that could be transacted will be transacted:

This printing method is presumably available because the electronic version is “dynamic” and provides multiple options in respect of the types of business to be transacted, and in the vast majority of cases where a blank proxy form will accompany the notice of meeting, the Province laudably wishes for all options to remain available.

Once the button is clicked and the proxy form is expanded, however, the following problem arises: none of the sections that may serve to give voting instructions to the proxy (e.g., “Section 1. Voting to elect candidates to vacant positions on the board that all owners may vote for”) appear on the same page as the section that defines the scope of the proxy’s authority (i.e., page 2).

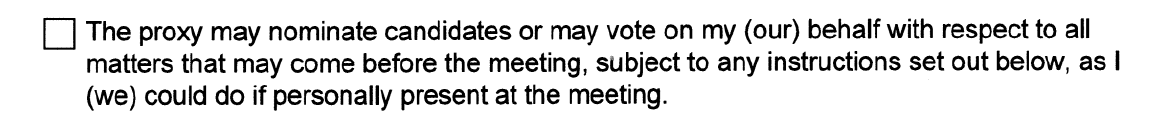

This problem creates a substantial risk in cases where the owner selects the following option, but the proxy tenders only the first two pages for registration:

In these cases, the chair of the meeting could, and perhaps should from an abundance of caution, properly declare the proxy form invalid on the basis that “Page 2 of 8” appears at the bottom of the same page, although exceptions could arise in cases where the chair receives evidence that subsequent pages did not contain voting instructions, or that the owner, rather than the proxy, detached the subsequent pages.[i]

That said, it is easy to imagine a situation in which the only thing that stands in the way of reaching quorum is the fact that a single proxy form consists of the first two pages and reliable evidence as to the contents and whereabouts of the subsequent pages is unavailable: while prudence would require an adjournment, the chair may be unable to resist the temptation, presumably under pressure from the group of people then assembled, to admit the defective form, give a ballot to the proxy and proceed with the meeting.[ii]

It thus seems only a matter of time, assuming it has not already happened, before an owner, somewhere in Ontario, is shocked to discover that his or her proxy voted by ballot, even though the owner had given instructions in the subsequent pages.

In that case, unless the proxy offered credible explanations as to why those pages were not tendered for registration at the meeting, and why the proxy failed to previously explain as much to the owner, the law would presume that the ballot cast by the proxy was inconsistent with the owner’s instructions, i.e., the results of the meeting could be called into question without the offending ballot having been identified.

[i] Evidence that fewer than eight (8) pages were included in the version that accompanied the notice of meeting would not be sufficient to overcome this defect because it would not answer the question raised by a proxy who has tendered only the first two pages.

[ii] The chair could, of course, refuse to give the proxy a ballot and count the proxy towards quorum only, notwithstanding the scope of authority given by the owner. In most cases, however, that would merely serve to provoke a different, more immediate type of dispute with the proxy.

Accordingly, for the purpose of preparing a proxy form to accompany the notice of meeting, we strongly discourage using the “Print Blank Form in Full” button (which, in our view, the Province should remove) and recommend that the corporation follow these steps instead:

- Select the box next to every type of voting that is expected to occur at the meeting (e.g., “Section 2. Voting to elect candidates to vacant positions on the board that only owners of owner-occupied units may vote for”);

- Click “Add item (+)” to add spaces for at least the number of positions available under each of “Section 1” and “Section 2”, as applicable; and

- Print the form using the normal print function or the “Print Form” button at the bottom of the last page.

It may take a minute or two longer to prepare the proxy form by this method but for the time being, it represents the only sure-fire way to avoid potential disaster.

© Deacon, Spears, Fedson + Montizambert, 2018. All rights reserved.

[1] The form was last modified May 8, 2018, according to its metadata.

[2] Evidence that fewer than eight (8) pages were included in the version that accompanied the notice of meeting would not be sufficient to overcome this defect because it would not answer the question raised by a proxy who has tendered only the first two pages.

[3] The chair could, of course, refuse to give the proxy a ballot and count the proxy towards quorum only, notwithstanding the scope of authority given by the owner. In most cases, however, that would merely serve to provoke a different, more immediate type of dispute with the proxy.